A walk along the banks of the Bridgewater Canal is a journey to the past and a glimpse into the future. Every stretch of the waterway has a story to tell us about human ingenuity, endurance and events that shaped both Salford and the world. This is a place of global importance, inspired by the vision of three men and the toil of hundreds of nameless heroes.

Radical thinking

Francis Egerton, the third Duke of Bridgewater, looked at his persistently flooded coalmines in the Irwell Valley and began to think big. Inspired by the canal he encountered on a trip to France, he realised that an artificial river could be a way of solving the problem within his mines and also providing the regions mills with the fuel they so badly needed. In turn, this would spark one of most pivotal moments in the story of human beings - the Industrial Revolution. Of course there would be problems - creating a canal was a massive undertaking, the geographical challenges were formidable and nobody had attempted canal building on such a big scale before. Luckily the Duke was someone who overcame problems using intelligence, hard work and a 'can do' attitude that would make the entire region a powerhouse.

Making it happen

The Duke was also clever enough to hire clever people to help him in his project. He and John Gilbert, his Estate Manager, developed a plan that would see the construction of underground canals running from the Duke's mines in Worsley to the mills of the north west. Going underground was a masterstroke - it solved drainage problems, provided a means for bringing the coal to the surface and offered a reliable source of water for the canal. At Worsley Delph, a wooden weir enabled the water to be lowered and raised, meaning no need for the opening and closing of gates, meaning faster transport. Politicians agreed with the scheme and the Duke was granted an Act of Parliament in 1759 to carve his waterway through the northern landscape. Clever minds are also flexible ones.

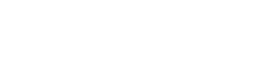

Brindley's Aqueduct

James Brindley was brought on board the project for his technical expertise. Brindley had already demonstrated his engineering prowess by solving a flooding problem at Wet Earth Colliery in Clifton. He suggested that the existing canal route could be changed to actually cross the River Irwell rather than avoid it. This would enable future expansion of the canal system and increase the ability to compete with the local river company by providing access to the most profitable areas of Cheshire and Manchester. It was an enticing idea, but how could it be achieved? Brindley, when describing his thoughts for the crossing, would carve a model from a piece of cheese. That cheese eventually became the Barton Aqueduct, the first of its kind in the world, and an immediate wonder of the region and the entire world. It wasn't just the initial design, but ingenious features that set it apart such as the stop gates that allowed for repairs whenever they were needed. Brindley faced ridicule from other engineers who couldn't share his vision. Even the man himself had doubts, hiding in a local hotel on opening day, scared of failure. But succeed it did. An official stamp of approval came in the form of ladies who made the aqueduct into a tourist destination.

An astonishing feat

The first beads of sweat from the canal builders' brows fell to the ground in September 1760. This was a tough endeavour for the navvies involved. The work took its toll but inspired the Duke with the pioneering idea of introducing sick pay, with the Duke supporting workers who fell ill on the job. It was one of the first of many breakthroughs in social progress that Bridgewater would inspire. Remarkably, the canal was open for business by 18 July 1761. Costing the equivalent of millions of pounds today, it was a truly astonishing feat for 18th century engineering. Over the following years further extensions were made to the canal, spreading its reach to Castlefield, Runcorn and Leigh. As well as the surface canal, there was also 46 miles of underground canal at Worsley Delph. Coal was carried in boats called 'starvationers' (because their ribs could be seen) and, once they reached the surface, they would by pulled by one horse or two mules. These boats were able to carry around ten times more coal than was previously possible by cart. In fact, the canal was so effective that the price of coal in Manchester fell by over half within a year of its opening. The Bridgewater was a main artery to the heart of the Industrial Revolution, allowing the region to be highly competitive and inspiring the rest of the world to adopt new ways of working. The canal also provided cheaper and more reliable transport for goods and raw materials. Cargo included maize, wheat and rice from Italy and Australia, hardwood, tea and coir fibre from Calcutta, lead from North America and paraffin wax from Burma. Passenger services also started in 1769 with a daily service between Worsley and Manchester. The two and half hour journey cost one shilling. But of course it was cotton that was king and the canal enabled the north west to lead the world in a universal product that would define the area for decades to come.

Profit and struggle

The nineteenth century proved to be a time of both profit and struggle for the canal. New forms of transport and increased competition led to price wars, new partnerships and compromises. The Duke of Bridgewater died in 1803 and left his estates to his nephew George Granville Leveson-Gower on the agreement that his son Francis would adopt his family name of Egerton. This was established under the Bridgewater Trust which would run the canal through most of the nineteenth century. Francis and his wife, Lady Harriet moved to Worsley in 1837 and found it to be "a God forsaken place in a state of religious and educational destitution". They did something about it by building churches and schools and taking women and young children out of the mines. An inspiration to many Victorian-era philanthropists. The genius of the canal attracted like-minded talent. In 1836, James Nasmyth had set up the Bridgewater Foundry by the canal side in Patricroft, making innovative tools cast from metal for the manufacturing and railway trade, including the steam hammer and the hydraulic press. An employment dispute at Nasmyth's foundry led directly to the establishment of 'Free trade in ability' as a universal principle of employment. The area became a crucible of new ideas. Friedrich Engels worked and lived in the area where his family had a small cotton mill. His experience provided material for the 'Conditions of the Working Class in England', one of the seminal works of economic history. Engels' descriptions of the appalling conditions faced by factory workers were vivid and angry, inspiring Karl Marx in his writings and leading indirectly to the rise of communism. The region has been defined by the downside of industrial progress that the canal also represented. It is no coincidence that the first trade unions were formed in the north west of England.

The arrival of the railways

During the 1820s canals were being criticised for being monopolies run by landed gentry that were failing to cope with increasing volumes of cargo. Many now looked to railways and, in particular, the possible construction of a railway between Liverpool and Manchester, assisted by Nasmyth's inventions. This was vigorously opposed by the canal owners who refused surveyors access to their land. But it was a futile fight against progress. In 1830 the new Liverpool to Manchester railway opened - a direct attempt to break the stranglehold that the Bridgewater Canal had on transport between the two cities. Built by Robert and George Stephenson, this was the first passenger railway in the world and, by the end of its first year, it was also carrying freight. Ironically it crossed over the world's first commercial canal at Patricroft - a symbol of its superiority when it came to carrying heavy materials. By 1844 The Times newspaper was reporting that the canal was to be emptied of water and converted into a railway. Nothing came of this scheme but times were changing rapidly. In 1855 approximately two million tons of coal still moved along the canal. By 1862 this figure was only half a million tons. However, there were happier events. In 1851 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, accompanied by the Duke of Wellington visited the canal and were given a trip on state barges that had been built specially for the occasion. It was reported that horses pulling the barges fell into the water after being frightened by the cheers of the large crowds.

Continuing innovation

In 1872 the canal was purchased by Bridgewater Navigation Company for £1,115,000 - using the first ever "million pound cheque". It was sold again in 1885 to the Manchester Ship Canal Company. By the 1880s the underground canal ceased to transport coal, although it continued to drain the mines until the closure of the last local pit in 1968. In 1893 the creation of a new Manchester Ship Canal meant that Brindley's original aqueduct needed to be removed, being too low for the vessels that would use the waterway. Instead the Barton Swing Aqueduct was constructed next to it - magnificent and groundbreaking in its own way and, perhaps, a symbol of an era that was coming to an end. Nothing on this scale had been constructed before and, the original aqueduct had to be destroyed before the new one could be tested. Happily it worked for the first of thousands of times and now the aqueduct, capable of holding 800 tons of water, is still working and is the oldest of its kind in the world. The 20th century proved to be a time of changing use for the canal. Newer forms of transport made it almost obsolete as a commercial waterway, but it still managed to inspire innovation. One notable achievement was the clearing of Worsley Works Yard to create Worsley Green. In essence this was the world's first regeneration programme. Commercial traffic finally ceased in 1974. The last cargo consisted of four barges of maize carried from Salford Docks to Kellogg's in Trafford Park.

Looking to the future

The Bridgewater Canal story is far from over. A new housing estate and park were developed alongside the Boothstown section in the 1990s. In 2011 the Bridgewater Canal Masterplan was adopted to transform the 4.9 miles of the canal that runs through Salford and make it a world-class tourist and heritage area. In 2014 £3.6 million was awarded by National Lottery Heritage Fund to revitalise the canal over the following four years, matched by a further £1.9 million from Salford City Council and major partners. This has seen the completion of towpath improvements to create an off-road pedestrian and cycle route, new seating, heritage interpretation and wayfinding signage, restoration of the historic sites of Worsley Delph and Barton Aqueduct and an events and activity programme to engage communities and volunteers and bring the story of the canal to life. As a place to enjoy and a place to learn, the Duke of Bridgewater's canal is still relevant over two hundred and fifty years after its opening. Its impact on the world is immeasurable; a symbol of hard work, amazing ideas and the sheer will to make things happen. Its place in the heart of Salford is as strong as ever.